Tactical Principles of the Liechtenauer SystemThe glosses of the Zettels which describe the Liechtenauer system can be interpreted a bit akin to a chess book - there are passages which describe general principles, others which deal with opening moves, then, as the situation beyond opening tends to get complicated quickly yet other sections describe how to fence from certain 'recovery points' (most importantly binds) and finally a set of passages describes a kind of 'endgame' when fencing is no longer viable and wrestling techniques become superior.The aim of the Liechtenauer system is to hit the opponent without being hit in the process. This sounds easier than it is in practice, because it needs to take into account opponents which may (through incompetence or recklessness) neglect their own defense just to hit. There are basically two ways to address this issue: First, you could never attack and always wait for the opponent to do so, making sure that each attack is met with a proper defence rather than potential suicidal recklessness. Ultimately you would then try to gain the initiative and counter-attack. Second, you could attack in a way that makes it hard for the opponent to make a meaningful simultaneous attack of his own. Technically this can be achieved by either using an action that blocks the most likely line of counterattack or by attacking with the aim of gaining control of the opponent's blade. In nearly all opening moves described in the manuscripts, either the first or the second condition is true and this does not seem to be a coincidence, the Liechtenauer system is designed to allow striking without unnecessary risks (cf. a modern view on this in Risk-averse Fencing). So how in detail is this accomplished?

Fight quickly to a bindThe first principle of the Liechtenauer system, and one of the most important ones, seems to be something like If you attack first, use a cut that simultaneously blocks meaningful lines of attack the opponent has.Vexingly enough, this isn't really explicitly stated anywhere, the closest thing to be found in the manuscripts is You must always boldly and without fear strike to one of the four openings and disregard what he employs against you, so he is forced to a parry. (1) but taken on face value this may easily be read as the opposite, i.e. an instruction to act suicidal and forego any defense. The reason I would read this differently is threefold: First, when describing what attack to employ against what guard (what 'breaks' what guard) the manuscripts usually list the very cuts which cover the attacker well. Once you follow that advice and use e.g. Zwerchhau against someone standing in Vom Tag, it actually is sound tactics to disregard what the opponent is doing and focus on your cut, because if you do it correctly at best you will hit, at worst you will be parried and have a bind. Third, the other principles of the Liechtenauer system - this time explicitly laid out - assume that you have reached a bind and tell you how to fence from there, and this is in fact the explicit context in which the quoted sentence occurs. Gain and keep initiativeThe manuscripts are fairly clear on the point that it is better to have initiative and force the opponent to react than to be just reactive:You should always come before the opponent, be it with cuts or thrusts, so that he has to parry, and from the bind you should fence quickly so he can not realize his own plans.(2) In fact, if you can, you should preferably be the one to start attacking: You should not wait and observe what he fences against you - fencers who do that and wait to parry tend to loose. (...) You should always be first with a cut or a thrust to an opponent's opening, so that he has to block you.(3) Yet 'coming before' is a bit more subtle - it is quite okay to wait for the opponent to attack if you react with a counter-attack rather than a simple parry because such a counter-attack returns the initiative to you. Like for the first principle, that requires techniques which simultaneously close off the opponent's possible lines of attack and deliver a cut or thrust. This, too, is spelled out explicitly: You shouldn't parry as the common fencers do. When they parry, they hold their point high or to the side, and that means they don't know what to do with it, so they lose. If you want to parry, at the same time use a cut or thrust and seek an opening, so you can win.(4)

Do a rapid series of follow-up attacksFrom a bind, you should immediately start to search for the next opening by winding the sword. This Winden seems to be a general term for motions of the sword which are constrained by contact with the opponent's blade. The problem that is to be solved here is that if you would pull back your sword from a bind to cut or thrust, this would immediately open a window for a counter attack.By winding your sword along that of the opponent, you always exercise a degree of control over what the opponent can do - but of course since the motions are constrained, the attacks that are still possible are of comparatively low energy. As such, they have to made in a way that is still threatening and you need to keep up the pressure, which is why the Liechtenauer system encourages you to focus on attacking the man, not the sword: Once you are parried, wind your sword to the next opening which you can reach, do not attack the sword, attack the man.(5) Much of the material in the manuscripts is concerned with laying out the precise follow-up technique you should use in a particular situation.

Feel the strength of the bind to decide how to followWhen an attack is parried, the swords touch for a moment. But what then?The opponent might pull back his sword as he thinks of counter-attacking immediately. Or he might intend to stay in the bind and push. In the first situation the bind is called 'soft' and in the second 'hard'. A soft bind you can expect to move aside, a hard bind you generally can not. This means what you can and should do requires to feel the strength of the bind. After a bind is reached - be it from a cut or a thrust - you need to find out whether the bind is hard or soft, and once you felt that you will know what to do next.(6) The strength of a bind might even change when the opponent realizes what you are up to, so you have to be ready to change plans as soon as you feel resistance. The general rule is that if the bind is soft, you thrust, if it is hard, you cut around. That makes sense, as the most likely reason for a soft bind is that the opponent is already preparing an attack of his own, so if you thrust quickly while making sure the angle of your thrust covers you (which is where the Winden comes in) you can land a hit first. On the other hand, if the opponent has committed strength to the bind, he cannot simply thrust - if the force is suddenly released, his blade will move aside, and he needs a moment to realize that and stop the blade - this gives enough of a time-window to do a quick cut around the sword (which is fast, but slower than a thrust). The general idea of the Liechtenauer system appears to be that if you can reach a bind, gain initiative and do a rapid-series of attacks that correctly take into account whether the opponent is weak or strong in the bind, eventually one attack will find its mark.

If you run out of space or time - sliceA slice does not require to pull back the arms as would be necessary to make a cut or thrust, so it can be very quick. In a high bind for instance (when fencers are standing fairly close, so this qualifies as a lack of space), to initiate a cut would require to leave the bind, step back and go forward again to attack. In contrast, a slice just requires to move the blade contact point from the hilt of the other sword to the wrist - and moreover, the slice can be used to gain space as it is just as effective when retreating, and it is safe in the sense that pushing the wrists of the opponent during the motion prevents him from attacking.

Watch for and exploit the opponents distance mistakesDistance is a convenient factor to hit without being hit, so naturally the Liechtenauer system makes use of it.Things are especially easy of you have the greater reach. This is the idea of Überlaufen. If the opponent attacks e.g. the legs, his hands would still be at hip level, and so his sword would be angled 30-45 degrees downwards. This angle reduces the effective range by 15-30%, which means that at a distance from which a cut on the head can hit, a cut on the legs may not. This can be exploited by simply retreating the leg and cutting high, which is what the technique is about. A consequence of this is that it usually is a bad idea to attack the legs as the initial move. Another distance mistake (which tends to be made by less experienced fencers) is that they cut short without intending it, for instance because they misjudge how quickly the defender can retreat. Such a short cut doesn't need to be parried since it has insufficient reach, and indeed, if it is not parried the blade goes astray, creating a split-second opening which can be exploited with a rapid counter-attack. This is the essence of Nachreisen.

Use 'safe' feintsThere are few feints mentioned in the manuscripts and as a rule they are safe in the sense that their decisive action blocks the line for a counter-attack.To see the difference, consider the following feint: The attacker initiates a cut at the opponent's head on the left side and halfway yanks the blade around to hit the opponent's right side. If the opponent defends with a block, his parry on the left will accomplish nothing because the attacker's sword is right and the cut will hit. However, if the opponent uses a counter-thrust, the cut will hit because the wrong line of attack is blocked, but the thrust will also hit because it is not opposed. Hence this is an unsafe feint. The feints described in the manuscripts are usually cuts made shorter than normal, so even if the defender falls for the feint and counter-attacks, the attacker's sword is in the right place to prevent this - and usually the idea of the feint is to get underneath the opponent's blade for a thrust which displaces it to a position from which no counter-attack can be done.

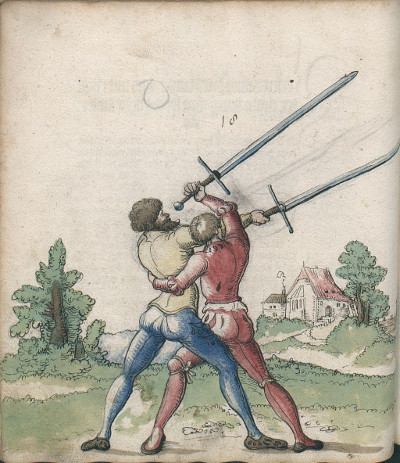

If needed abandon the sword and wrestle before getting stuckWhen the two fencers are very close and the swords are in a bind, the Liechtenauer system appears to favour the surprise effect generated by partially (with one hand) or fully abandoning the sword and try to wrestle the opponent to the ground over attempts to retreat.The prerequisite is that the relative position is such that the attacker can step with one foot behind the opponent and then move his body next to him - in this position, grabbing the opponent with a free hand and pushing him backwards such that he falls over the leg behind him is a feasible (and fairly agressive) tactic. The manuscripts describe multiple wrestling and even sword-taking moves, so this seems to have been of some importance.

SummaryWhile this is never spelled out explicitly, the Liechtenauer system has devoted quite some effort to the question of how to attack safely, i.e. how to avoid the scenario that a reckless opponent is successful with simply neglecting his own defense to land a hit no matter what.In the offense, the system is relies on attacks that 'break' guards, i.e. block the most obvious line for a counter-attack. In defense, counter-cuts and counter-thrusts are the tool of choice. Unlike Joachim Meyer, Liechtenauer does not appear to believe in the value of blocks to gain time. Unlike Fiore and Meyer, the Liechtenauer system also does not rely much on cuts against the blade (it is explicitly said to 'attack the man, not the sword'), presumably because Durchwechseln und Zucken followed by a thrust are fairly effective as counters to blade-attacks. Perhaps not surprising for a fencing system having to deal with sharp weapons, the approach to control the opponent's blade or to block his line of counter-attack is fairly safety-conscious. Still - the agressive way of using counter-attacks is not for the faint of heart: If you're fearful, you should not take up fencing --- if you are weak-spirited you will lose however artful your techniques are.(7)

Original quotes (English translations above by myself): (1) das du alweg mit einem hau oder mit einem stych hinlich, on alle vorcht, solt reinen der vir plos einer Zu welcher du am pestenn kumen magst, und acht nicht was er gegenn dir treibt oder vicht, Domit zwingstu den man das er dir versetzen mus (2) Das ist das du vor solt kumen alweg es sey mit dem hau oder mit dem stich, Ee wen er Und wen du ehe kumpst mit dem haw oder sunst das er dir versetzen mus, So arbait Indes behendiglich in der versatzung fur dich mit dem schwert, oder sunst mit anndern stuckenn: so mag er zu kainer arbeit komen, (3) Das ist wen du mit dem zu fechtenn zu im kumpst, so soltn nicht still sten und auff sein haw sehen noch wartn,was er gegen dir ficht Wis das alle vechter, die do sehen und warten auff aines andern hau, und wollen anders nicht thon wen vorsetzen, die bedurffen sich sollicher kunst gar wenig freuwen, wenn sie ist vernicht, unnd werdenn do pei geschlagen (4) Das ist das du nicht versetzen solt als die gemeinen vechter thun Wann sie vorsetzn so haltenn sie irn ort in die hohe oder auf ein seitn Unnd das ist zuversten das sie in der versatzung mit dem ort nit wissen zusuchn Darumb werden sie oft geschlagenn Oder wen du versetzn wild, so versetz mit deinem hau oder mit deinem stich und such inndes mit dem ort die nechst plos so mag dich kein meyster on sein schadn geschlagn (5) Unnd wen er hat versetzt, so such pald in der versatzung mit dem windn am schwert aber die nechst plos, unnd also raume alweg der plossenn des mans unnd vycht nicht zu dem schwert (6) Daß ist dz du gar eben mörcken solt wann du dir aine mitt ainem haw oder mit aine stich oder sunst an din schwert bintt bindet ob er am schwert waich oder hört ist vn wenn du das enpfunden hast So solt du In das wissen welchses dir am beste sey (7) Aber erschrckstu gern so saltu die kunst des fechtens nitt lerne - Wann ain blöds verzags hercz daz tut kain gut wann es wirt bey aller kunst geschlagen

Peter von Danzig's gloss on Wiktenauer

Back to main index Back to Swordfighting Created by Thorsten Renk 2025 - see the disclaimer, privacy statement and contact information. |