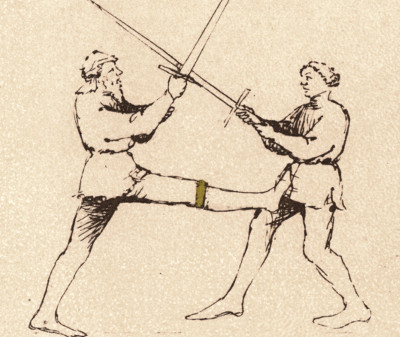

Historical Swordfighting Systems - an OverviewFioreThe illustrated Italian fencing manuscript Fior di Battaglia ('The flower of battlle', around 1400) by the knight Fiore Furlano de'i Liberi is one of the earliest fencing manuals describing longsword techniques that has survived. The manuscript itself isn't particularly focused on longsword - it treats many kinds of combat, including wrestling, the use of the dagger and the one-handed sword or mounted combat.The Fiore system appears to aim at being applied in actual wars. Not only does it describe encounters of different weapons (longsword vs. spear) or describe techniques which are chiefly of use when faced with multiple opponents such as the volta stabile (a quick turn without changing position), but it also includes techniques which are brutally effective, but have little resemblance to lofty ideas about noble knightly combat - for instance kicks into the groin or to the knee:

> >

Out of these, close-play is chiefly wrestling with the blade and less what people would usually call 'fencing' (this comment is not meant to dismiss close-play - in a real swordfight there is an obvious need to deal with such situations). Of the about 15 wide-play techniques, only one (the punta falsa) is a clearly offensive technique and can be used to attack, five (rompere di punta, scambiare de punta, colpo di villano, defence against low attacks and the diagonal parry) are clearly defensive and require the opponent to act first and the rest is neutral -the techniques start from blades crossing but either combatant can then initiate them. My general impression is that Fiore is originally meant to give noble officers an edge in war when they are up against opponents whose idea of swordfighting is to do the obvious - hit hard and fast and keep cuts coming. From my own experience I can say that Fiore techniques work really well against enthusiastic beginners because they often get confronted with surprising developments they simply hadn't thought of - like a grab for the blade, or half-swording (gripping the own sword on the handle and on the blade to get a better lever-arm).

The Fiore Manuscript on Wiktenauer

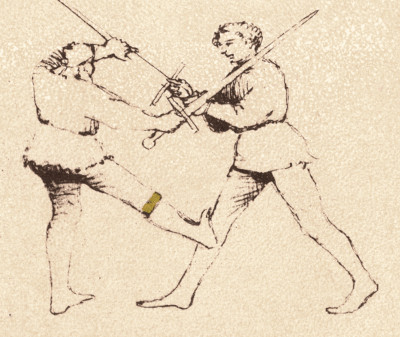

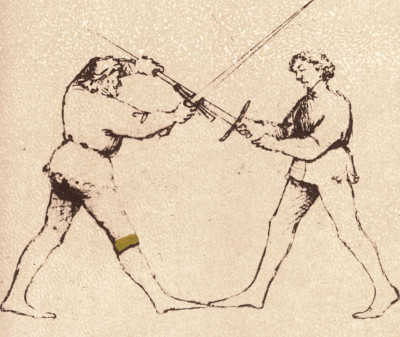

VadiPhilippo di Vadi Pisano's manual De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi ('On the Art of Swordsmanship', from 1487) clearly owes a lot to Fiore (many illustrations are identical, although Fiore usually provides more detaild glosses). It is a longer work, not only dealing with longsword but also with poleax in full armour, longsword in full armour, spear and dagger (although some of these sections are very short). The manual is Italian and written in verse form, but what makes it quite distinct from Fiore's work is that it gives some insight into the basic fencing.Like Fiore, Vadi lists various guards and lays out the the six basic cuts (descending, ascending and horizontal, left and right) and the thrust, but then he follows with a longer text section on how fencing in middle distance (mezza spada, a distance approximately when both swords cross at the middle) should be done. What he presents is in essence the same idea Meyer advocates a century later - hit fast, change the direction of the attack frequently, use feints to confuse the opponent. He acknowledges that fencing at this distance is very fast, so not many actual sequences are given. What is fairly remarkable at this point however is that he describes an inverted footwork, i.e. one should do a lunge with the right foot for a strike from the right side (rather than a passing step that starts out with left foot forward as is more traditional). Also, he takes some time to present the mezzo tempo ('half tempo') strike, a fast cut 'from the wrist' which, similar to the Liechtenauer concept of the Meisterhau, strikes and parries at the same time. However, where Meyer presents a detailed theory on how to best enter such a fast exchange while avoiding double hits, Vadi more or less resorts to general advice like as the opponent lifts the sword, grab the tempo, don't hold back - which in itself isn't overly helpful. The illustrated section on longsword is fairly similar to what Fiore presents for zogho stretto, i.e. close play (if you look closely, the second technique depicted, the punta falsa, is the same as from the Fiore manuscript above).

Tactical Principles of the Vadi System Vadi's Fencing Manual on Wiktenauer

LiechtenauerWhile Johannes Liechtenauer is arguably one of the greatest longsword fencing masters in the German tradition, there is no surviving fencing manual authored by him. Instead, what is available are illustrated glosses of Liechtenauer's zettels - verses probably intended as mnemonic aids for students, for instance (Pseudo)-Peter von Danzig has published such a gloss in 1452.These manuscripts are not a systematic introduction to the art of longsword-fencing (or one-handed or mounted fencing which is also part of them). For starters, they likely assume that the student knows some basic fencing like cuts, thrusts, blocks and legwork. On they other hand, they occasionally compare to 'what common fencers do' (and what the Liechtenauer student should not do), so - just as Fiore - the techniques described are intended to be special. The opponent assumed is someone who fences with a longsword in single-combat and may even know how to cut an attack away or to feint, but is not himself familiar with the Liechtenauer system. The manuscripts are loosely organized according to techniques - plays from the various special cuts like Zwerchhau or Schielhau are grouped together, general advice is given in between, usually a rhyme introduces a new section and the following gloss explains the meaning. While this is never stressed clearly, one does get the feeling that Liechtenauer follows an overarching philosophy how attack and defense in a swordfight should be organized and the techniques and sequences described illustrate general principles. For instance, one of the central concepts is the idea of master cuts that 'break' certain guards, i.e. if you use this cut to attack someone standing in a certain guard, he cannot easily counter because the line for the counter is closed by the master cut. This makes it possible to attack 'safely', i.e. without running the risk of simultaneous hits.

> >

> >

Like Fiore, the manuscripts devote quite some space to close play in terms of various grappling and throwing as well as sword-taking moves, but it lacks the more brutal moves of Fiore like joint-locks. Tactically, the Lichtenauer system is quite complex and versatile. For modern applications, the obvious gap is that there is not overly much guidance how to fence an opponent who uses Liechtenauers techniques himself - only few of the sequences that are described deal with such a situation. Tactical Principles of the Liechtenauer System

Peter von Danzig's gloss on Wiktenauer

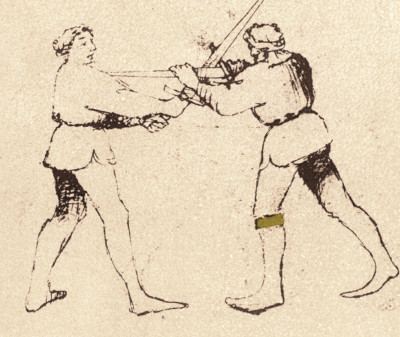

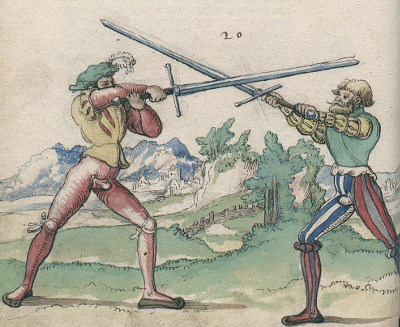

PaurenfeyndtOne of the lesser known fencing masters, Andre Paurenfeyndt published his fencing manual Ergrundung Ritterlicher Kunst der Fechterey ('A Study of the Chivalric Art of Fencing') in 1516. Formally he is part of the Liechtenauer tradition amd many of the original verses appear in his work, but there are also descriptions of techniques that resemble elements of Fiore, for instance the use of the Eisenpfort - porta di ferro parry, the peasant strike colpo di villano or diaginal upstrikes against an attack.Speaking politely, Paurenfeyndt isn't the most gifted teacher around which makes the manuscript difficult to read. While he introduces new names for the various guards (for instance Lichtenauer's Vom Tag he calls Hochort), the verse sections continue to use the old names and even the prose glosses occasionally fall into them. There are illustrations, but the relation to the text remains a bit hazy. While the verses would instruct to remain in binds and follow with techniques like duplieren and mutieren, the sequences described by Paurenfeyndt usually pull back from binds for another attack.

> >

Perhaps not unexpected, the manual also contains a fair share of pommel strikes, grappling and throwing techniques for close play, supplemented by techniques for holding an opponent down when he is on the ground. It's hard to get a sense for what tactics Paurenfeyndt actually envisioned - clearly he deviates from Liechtenauer in places, but apart from sequences and the quoted Liechtenauer verses, he hardly describes his own idea of fencing. Perhaps then the manual is best understood as a collection of tricks and techniques that have proven useful in exchanges- and of course it provides an interesting historical data point between Liechtenauer and Meyer. Paurenfeyndt's manual on Wiktenauer MeyerJoachim Meyer's Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens ('Thorough Description of the Art of Fencing') of 1570 is a long and systematic introduction to the topic covering not only longsword (which Meyer regards as the basis of all fencing) but also dusack, rapier, dagger and polearms.By Meyer's time, fencing is no longer a necessity in war but is well into the transition to a sports activity. Thrusts are no longer done and no pommels are hammered into faces, so fencing for Meyer is primarily an exchange of cuts and while his system is based on Liechtenauers work, he finds little use for the old thrusting guards that provide poor opportunities for quick and powerful cuts. Meyer lays out longsword fencing for a complete beginner - he starts with basic elements like guards, cuts and parries, then discusses the general idea of an exchange as approach, attacks and retreat and only in the end gets to specific sequences from the various guards or from the master cuts like in the Liechtenauer Zettels, At the heart of the system is the idea of attacking in longer sequences of cuts moving from one opening to the other while keeping the opponent defending all the time. By executing some of these attacks for real, some only as feints, the opponent is not being given much opportunity to counter. If the opponent manages to get a defensive cut in, a bind usually develops and Meyer argues that in the bind, a fencer can similarly attack in many different ways around the contact point and thus keep the initiative. In the defense, Meyer takes a somewhat more positive view of simple blocks than Liechtenauer does. In essence he argues that while blocking an attack doesn't gain a fencer the initiative, it does gain the time to prepare a more effective defence like a cut to the blade - from which a counter attack can start.

The system is really complex, introducing lots of different ideas, cuts and sequences including sophisticated double-feints and it does not assume that the opponent has never heard of Meyer's system. For a modern practitioner, the possible achilles heel is the lack of thrusts - counter-thrusts can be done very fast, and the manual offers no guidance what to do against them, so if thrusts are to be used, the system still has to be supplemented by ideas from Liechtenauer (which is no big issue as it is clearly based on Liechtenauer's ideas). Tactical Principles of the Meyer System Meyers manual on Wiktenauer Back to main index Back to Swordfighting Created by Thorsten Renk 2025 - see the disclaimer, privacy statement and contact information. |