Lagrange point orbitsBefore, we have discussed two types of stable orbits of planets around binary stars, the 'Janus' and the 'Helliconia' type. However, there is in fact one more type of stable orbit in a three-body system which is of neither type - the planet can be on one of the stable Lagrange points.At a Lagrange point, the gravitational forces of two heavy masses balance with the centrifugal force of a third light body, thus the light body being exactly at the point can orbit undisturbed (and a satellite can be 'parked' there with minimum fuel requirements). The L1 to L3 points along the axis of the two heavy masses are however unstable, a planet orbiting there would leave the Lagrange point if it is even slightly perturbed. This is not necessarily so for the L4 and L5 points. At the L4 and L5 points, the planet orbits 60 deg away (either ahead - L4 - or behind - l5) from the lighter star on the same circular orbit around the heavier star, the two stars and the planet thus form an equilateral triangle. Since both stars have the same distance to the planet, the resulting force vector of the gravitational force is a function of their mass ratio only. The result is that the force points through the system's barycenter, i.e. the planet can orbit as if it would simply orbit the system's center of gravity. If the mass ratio between heavy and light star is 24.96 or more, the L4 and L5 points are actually stable, i.e. an orbital perturbation brings the planet back to the Lagrange point - so orbiting on the L4 or L5 points is a class of stable orbit not discussed so far. From the point of view of 'interesting' exoplanets, most Lagrange orbits do not qualify however. By definition the distance to both stars is equal and then the mass difference of 25 or more translates into huge luminosity difference, so the irradiation will usually be almost entirely determined by the heavy star. The same is true for moons orbiting at the Lagrange points of star and planet systems - the planet is so far away that it doesn't influence the moon in any significant way (Jupiter's Trojan moons are as far away from the planet as Jupiter is from the Sun - Jupiter is merely a dot in the sky). So there is little to explore beyond orbital mechanics that cannot be simulated otherwise.

Sapphire, Ruby and EmeraldThe Emerald system is pushing the boundaries of creating interesting dynamics. It consists of Sapphire, a hot, B-class star of 15 solar masses that is orbited by a much smaller, 0.6 solar masses star, Ruby. However, Ruby is an old star and is near the end of the red giant branch, so its radius and luminosity are greatly increased as compared to a same mass main sequence star (how these two stars would end up orbiting each other is a mystery of its own).The planet Emerald orbits at the L4 Lagrange point, and since the mass ratio of 25 is just above the stability limit, the orbit is stable, but due to the perturbations of the slight orbital eccentricity fairly chaotic. Because Ruby as a red giant has increased luminosity, it contributes more than 10% of Emeralds radiation budget (and in fact is the larger object in the sky - while Sapphire appears as a brilliant dot of light, Ruby appears 50% larger than the Sun). Here is the definition file:

The keyword lagrange_point, combined with a missing semimajor axis, tells the software to place the planet into the same orbit as the star, just 60 deg ahead). Note that the code will not try to determine a Lagrange point numerically - whatever the eccentricity is and whatever other bodies are simulated, the L4 point will be assumed to be 60 deg ahead in the star orbit (the point may not be stable at all in reality).

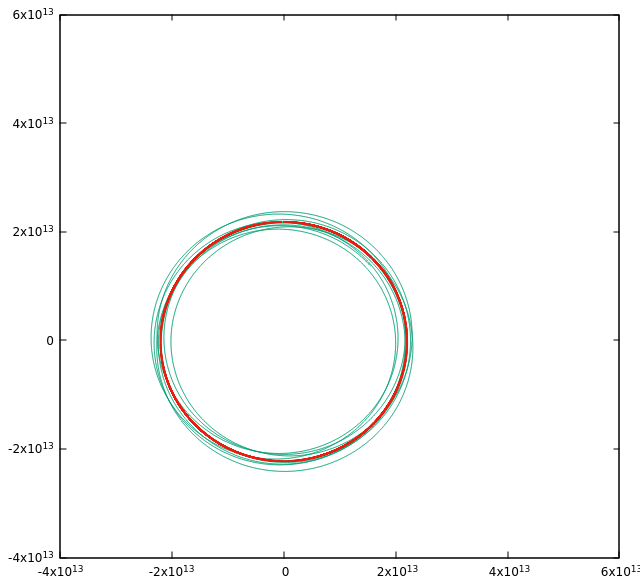

Orbital stabilityFollowing Emerald for 4500 years (or about 10 orbits around Sapphire), it is apparent that the orbit 'wobbles' a bit around Ruby's orbit, but remains more or less stable (this of course gives rise to interesting and unpredictable variations in the average temperature).

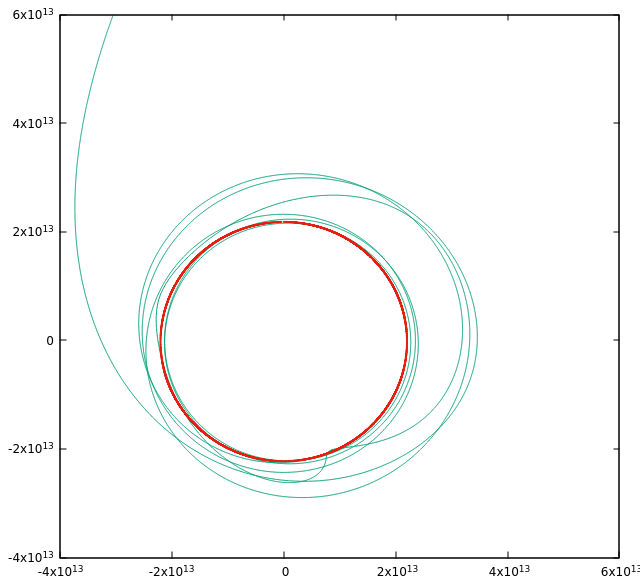

However, if Emerald would be placed away from the Lagrange point, the orbit is clearly unstable and the planet would disappear into interstellar space after a few orbits (so the Lagrange point is indeed a special location). Such a placement can be achieved by adding the keyword lagrange_delta_phi which shifts the placement angle away from 60 degrees.

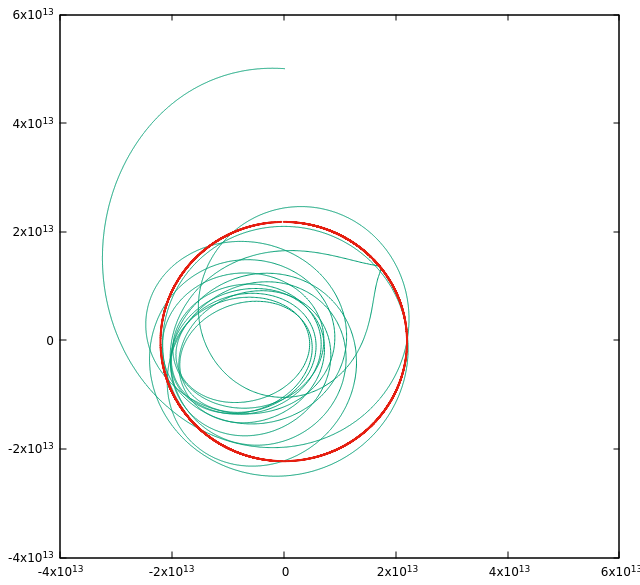

Let us take a look at the effect of the stellar mass ratio next. If the mass of the orbiting star is heavier such that the ratio is 12.5, Emeralds orbit clearly becomes unstable even when the planet is initialized on the Lagrange point. The perturbations are simply too large in this case.

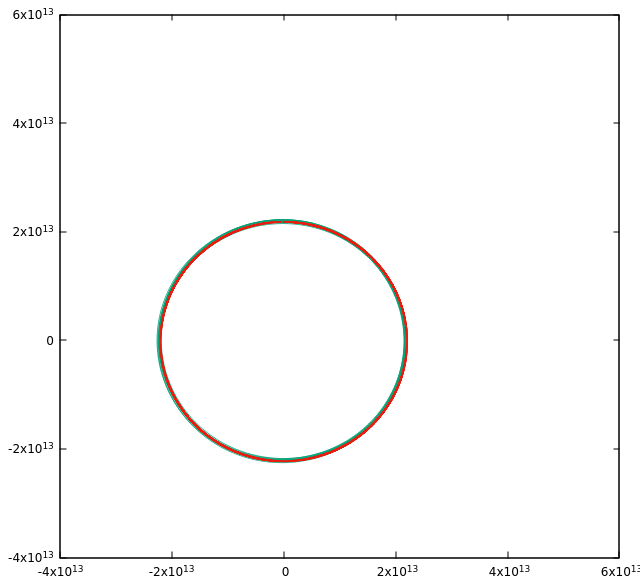

On the other hand, if Ruby's mass is reduced to 0.3 solar masses, the ratio is 50 and Emeralds orbit is much more regular and aligned with that of Ruby.

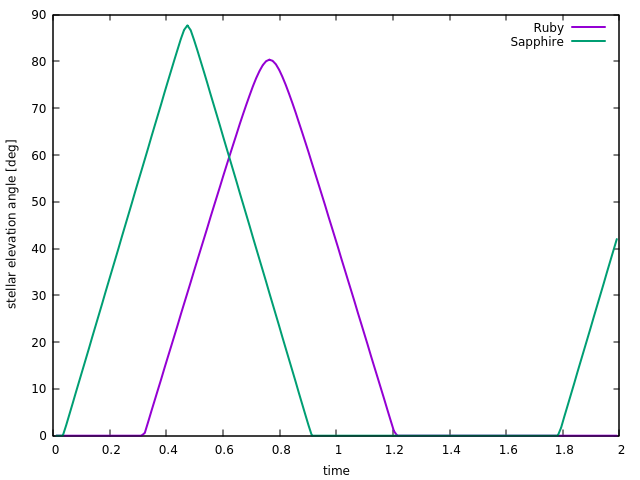

Day and nightSince the three worlds form an equilateral triangle, seen from Emerald the two suns in the sky are always the same angular distance away from each other, i.e. 60 degrees. This is true no matter where in the orbit the worlds are Seen from the equator of Emerald, first Sapphire rises and starts the bright phase of the day, somewhat later Ruby rises (but its presence would not be very prominent) and when Sapphire sets, a long second evening in red-golden light is brought by Ruby.

Continue with Lagrange world thermal properties. Back to main index Back to science Back to worldbuilder Created by Thorsten Renk 2026 - see the disclaimer, privacy statement and contact information. |